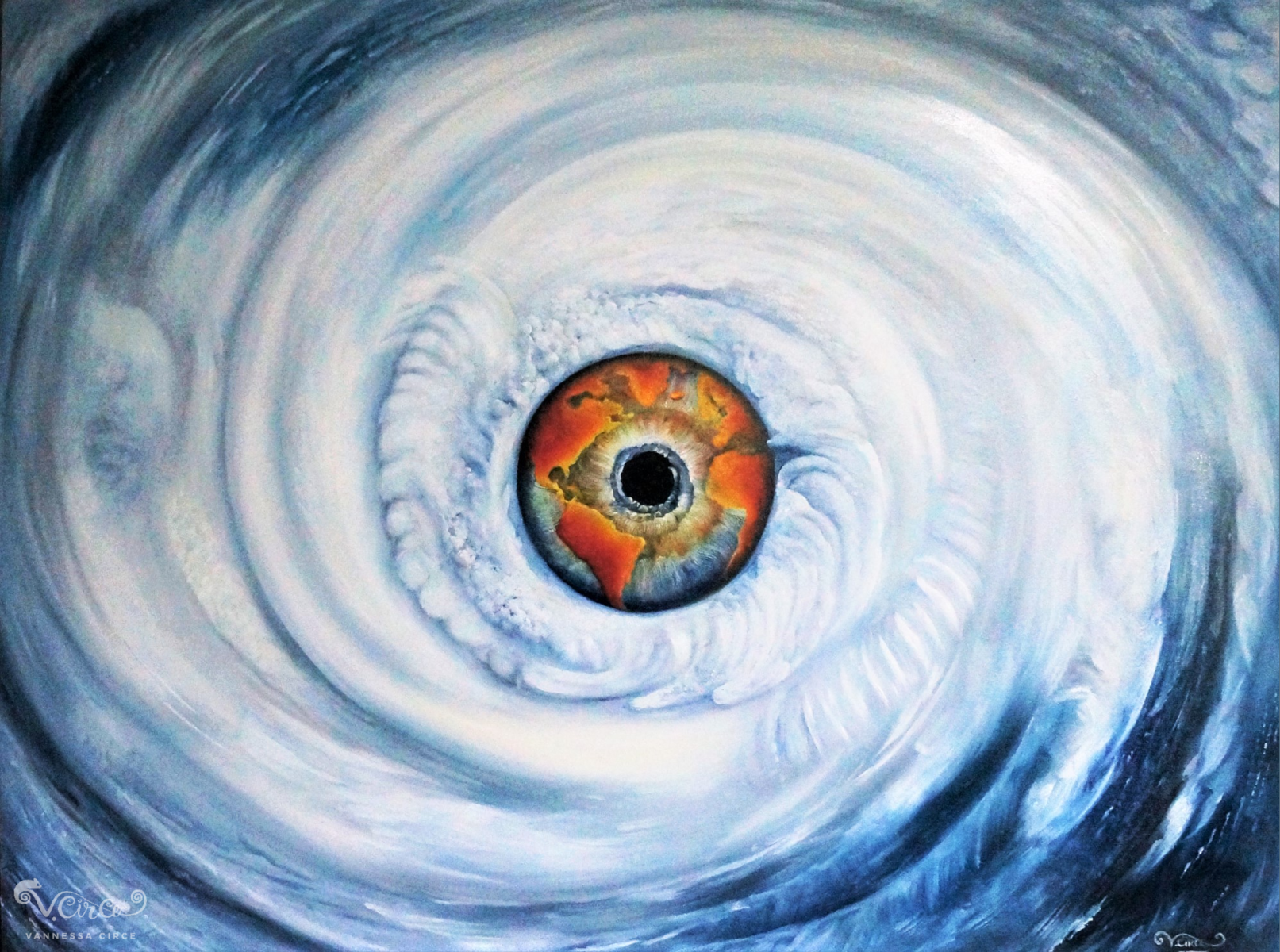

Oil on Canvas

30″ x 40″ – April 2020

Energy is neither created nor destroyed, it goes through transitions of form and is contained within the forces of nature. Humans continue the vital search for sustainable ways to release and harness this energy.

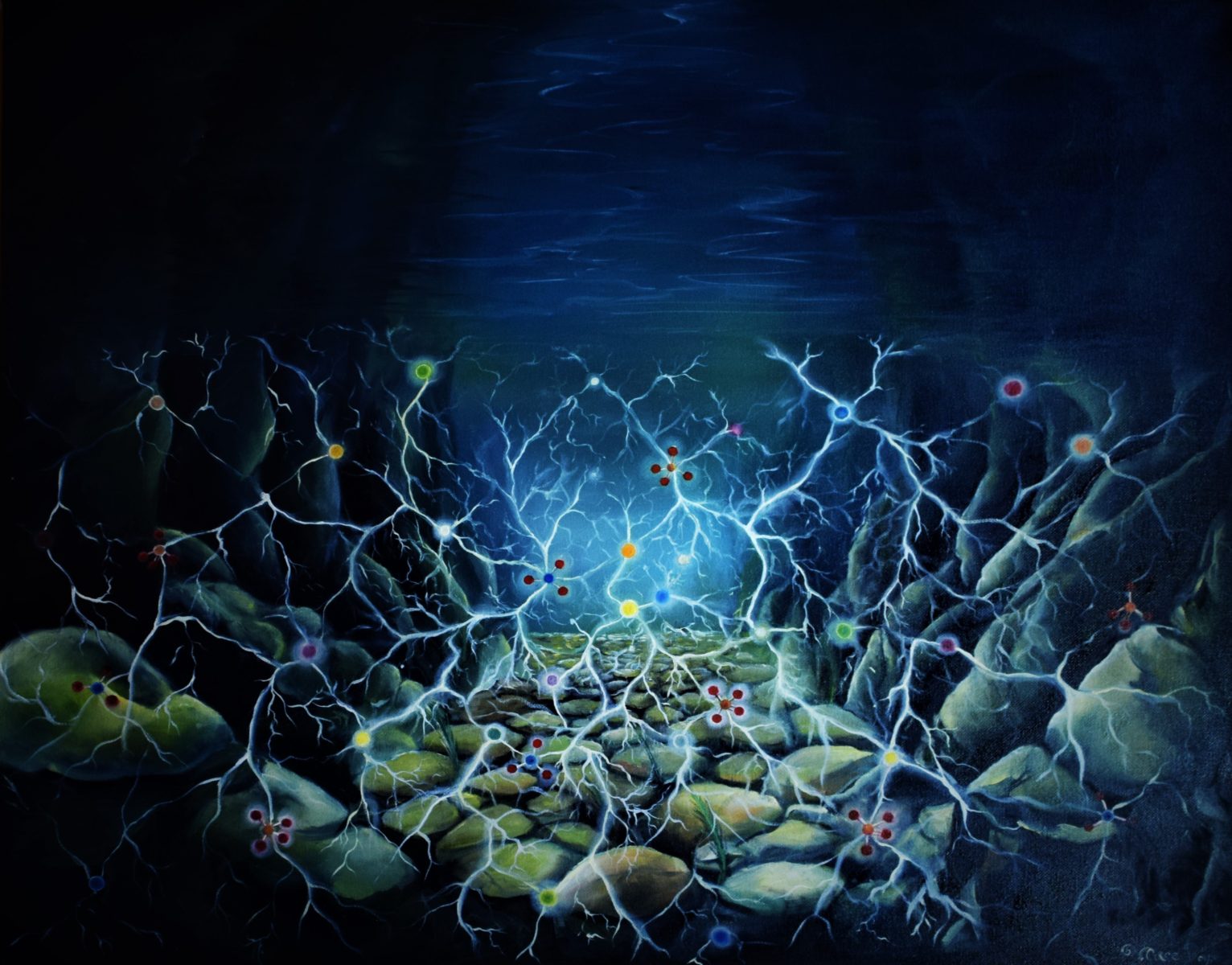

Oil on Canvas

24” x 28” – March 2019

An important way of understanding the content and quality of fresh water bodies and drinking water is by estimating the total number of dissolved solids in the liquid. This can be done by measuring the electrical conductivity of the water, which detects the electrical current passing between dissolved ions. These ions have positive or negative charges, and can be salts or metallic compounds or elements. While a certain level of conductivity in a fresh water body is normal (in salt water it is naturally very high), and varies between water bodies, any significant temporal changes in conductivity can represent contamination and/or degradation of the water, through human activities such as mining and intensive agriculture, or natural processes such as the erosion of soil (which also may be caused by human activities such as deforestation).

This painting communicates the concept of the electrical conductivity of freshwater through displaying a variety of chemical compounds that represent dissolved ions within a flowing river.

Oil on Canvas – 24” x 24”

May 2020

Inspired by the vital ecosystems, endemic plants and traditional food systems that have kept us and other species alive and in balance for millenia. The painting depicts the essential high-Andean paramo ecosystem, and traditional Andean crops that Indigenous ethnic groups have cultivated for generations.

Oil on Canvas

48” x 54” – June 2019

Despite an increasingly robust global body of evidence that shows secure land-rights for traditional communities translates to lower rates of deforestation and land degradation, a disproportionately low amount of attention is being given to utilizing these communities as part of the solution to profound global challenges; as stewards of the forests, protectors of ecosystems and mitigators of climate change.

Only 10% of collective lands, including those of indigenous groups around the world, have recognized legal titles, essentially ignoring their tremendous global environmental and cultural value. Even worse, these groups and territories are increasingly vulnerable to threats, displacement, deforestation and exploitation of the natural resources of their territories.

In many of the most heavily forested and biodiverse countries, such as Colombia, Brazil, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Philippines and Indonesia, indigenous communities and their leaders who speak up for their rights, and oppose the often connected commercial (both “legal” and illicit), political and militant actors who want to exploit or expropriate their territories, face threats and violence, and all-to-frequently displacement or death. As the troubling case of Colombia shows, it is not enough to just put indigenous rights in writing, even in a national constitution; land rights and tenure must be secure, and security must be ensured so these communities can safely and sustainably manage their lands and speak up for their rights in the present, with an eye towards the future.

Three forest-dwelling indigenous leaders from different parts of the world hold their ground along with emblematic forest species, against destructive intrusions into their territories.

Oil on Canvas

36” x 48” – May 2019

Hydroelectric dams impact local ecosystems regardless of their size or geographic location, but lowland tropical ecosystems can suffer the most wide-ranging negative impacts from large hydropower constructions. It is in these rich tropical forests and floodplains that so much of the world’s biodiversity and native populations reside, and also where carbon is stored in large quantities in the soil and vegetation, which helps buffer the world against rapid climate change. In mighty river basins like the Amazon in South America, the Congo in Africa and the Mekong in Southeast Asia, current and planned construction of large dams in their tropical ecosystems are due to cause extensive damage to aquatic and terrestrial species, local communities and global and regional climate patterns.

This painting depicts a flooded and fragmented Amazonian ecosystem, caused by a hydroelectric dam in the background. The golden catfish and tucuxi river dolphin represent species whose long migratory ranges have been blocked. Decaying organic matter and accumulating sediment are producing bubbles of methane. An indigenous hut represents displaced indigenous communities, and a dead monkey communicates the impact that these constructions have on terrestrial biodiversity.

Oil on Canvas

24” x 36” – May 2019

For many, glyphosate conjures up images of vast industrial monocultures, genetically engineered crops, and huge global industries and corporations. But glyphosate in particular, as the world’s most widely used herbicide, has and continues to have many other applications, and its full impacts on human and environmental health are poorly understood.

No matter on which side of the “GMO debate” one falls, or how toxic or carcinogenic one believes glyphosate itself to be, or how long glyphosate residues actually stay on plants and within different types of soils, any fair assessment shows that there have been grave misuses and overuses of this “organophosphorus ” chemical compound (specifically a “phosphanoglycine”), with insufficient consideration for its potentially far-reaching consequences.

The indiscriminate aerial spraying of glyphosate in Colombia under the umbrella failure of “Plan Colombia” that was aimed at the eradication of coca plantations (coca being the base ingredient of cocaine), is a particularly egregious example of the misuse of glyphosate. Incredibly, despite the failures of Plan Colombia in curtailing cocaine production, and the poorly understood but widespread environmental and social impacts that were wrought by the aerial spraying of glyphosate, as of 2019 the Colombian government, supported by the United States, is re-initiating the “strategy” of aerial fumigation of glyphosate.

A symbolic depiction of the wide ranging impacts of aerial glyphosate spraying in Colombia. The drift of the spray can kill not only the targeted coca plantations, but also endemic and medicinal plants, while entering water bodies, and causing other potential health and environmental impacts.

Oil on Canvas – 30” x 40”

January 2019

In Colombia, land is power. The more than half-century long civil war (which despite international proclamations and nobel peace prize adornments, still has not reached its resolution), was more than anything about the control of land. More than seven million people have been internally displaced during the conflict, which is the most in the world (Syria is second).

The Colombian constitution of 1991 is recognized as one of the strongest legal documents in the world in terms of guaranteeing indigenous rights, to land and social participation. Nonetheless, an often absent and always corrupt government rarely fulfills the obligations of the constitution, and indigenous groups and leaders who stand up and speak up for their territorial rights are often silenced, permanently.

Colombia has become the world leader in assassinations of social and environmental leaders and human and land rights defenders, a trend that is only growing since the signing of the “peace agreement” between the Colombian Government and the FARC (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia) in 2016.

Here a young indigenous Nasa leader is being silenced by dark forces while trying to hold on to his land.

Oil on Canvas

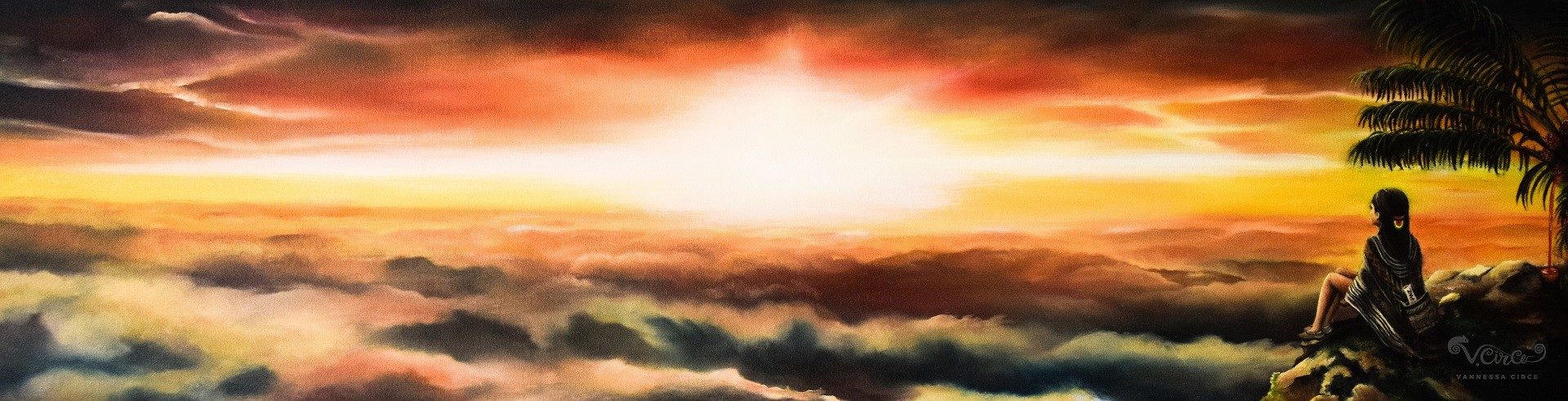

27” x 54” – August 2018

While Colombia has several clear direct drivers of land cover change and deforestation, both legal and illegal in nature (though the line between the two is often blurred), some fundamental social and governmental mechanisms and infrastructure developments are likely the most important drivers of deforestation in Colombia, though they are indirect in nature and hard to quantify. The laws of land titling encourage the clearing of land, regardless of whether or not that land is converted from forest into something commercially productive or sustainable, and whether or not that land was gained through violence and forced displacement of people with or without legal tenure to the land. Much “land-grabbing” is done by smallholder farmers, who then sell the newly deforested plots in order to consolidate them into large ranches owned by wealthy landowners. In terms of land distribution, Colombia has one of the world’s highest levels of inequality, with 13 percent of the landowners holding 77% of the land. 44.7% of Colombia’s rural population is estimated to live in poverty.

Road construction, as in many other parts of the world, has also opened up frontiers that then lead to legal and illegal activities that directly lead to deforestation.

This painting displays some of the most identifiable drivers and impacts of deforestation in tropical forests, which are the most biodiverse terrestrial habitats on the planet. Road construction, cow pastures, forest fires, oil extraction, gold mining and palm and soy monocultures, are all portrayed, as are habitat fragmentation, biodiversity loss and carbon emissions. The drivers themselves are driven in large part by global supply chains and consumer demand for inexpensive products that do not factor in their true costs.

Oil on Canvas – 40” x 40”

April 2018

The extremely unique high-altitude ecosystem of the “paramo” is symbolically displayed in this painting, through it’s vulnerable flora and fauna.

Oil on Canvas

40” x 48” – April 2018

In the harsh desert landscape of La Guajira, Colombia, water has always been a scarce and precious resource. In this extreme environment, the local Wayuu people have always practiced a system of water capture, storage and conservation in wayuu-made reservoirs called “jagueyes.” These jagueyes are used to sustain humans, animals and agriculture alike, in historically predictable times of dryness.

Present day La Guajira is suffering from an extreme scarcity of non-contaminated water. The Wayuu indigenous people, their crops and animals, and the endemic wildlife of the “Cerrejon Formation” region, are becoming ill, dying and being displaced at alarming rates.

This environmental and “humanitarian crisis” results from a complex mixture of global climate change, unsustainable land use, corrupt and conflicting interests of national and local governance along with national and international governmental and non-governmental organizations, terrible water and resource management, inadaptability of traditional beliefs to present circumstances, and economic interests of multinational corporations and the global supply chains that support them. One of the world’s largest open-pit coal mines, El Cerrejon, a multinational venture that does it’s fair share in exacerbating our planet’s global problems, has helped to ensure the decimation of the once highly autonomous Wayuu in La Guajira, especially through the depletion and contamination of their jagueyes, groundwater, and the Rancheria river.

The crisis in La Guajira and with the indigenous Wayuu helps to clearly illustrate what can happen when these conflicting and often malicious interests are thrown upon a vulnerable environment and people.

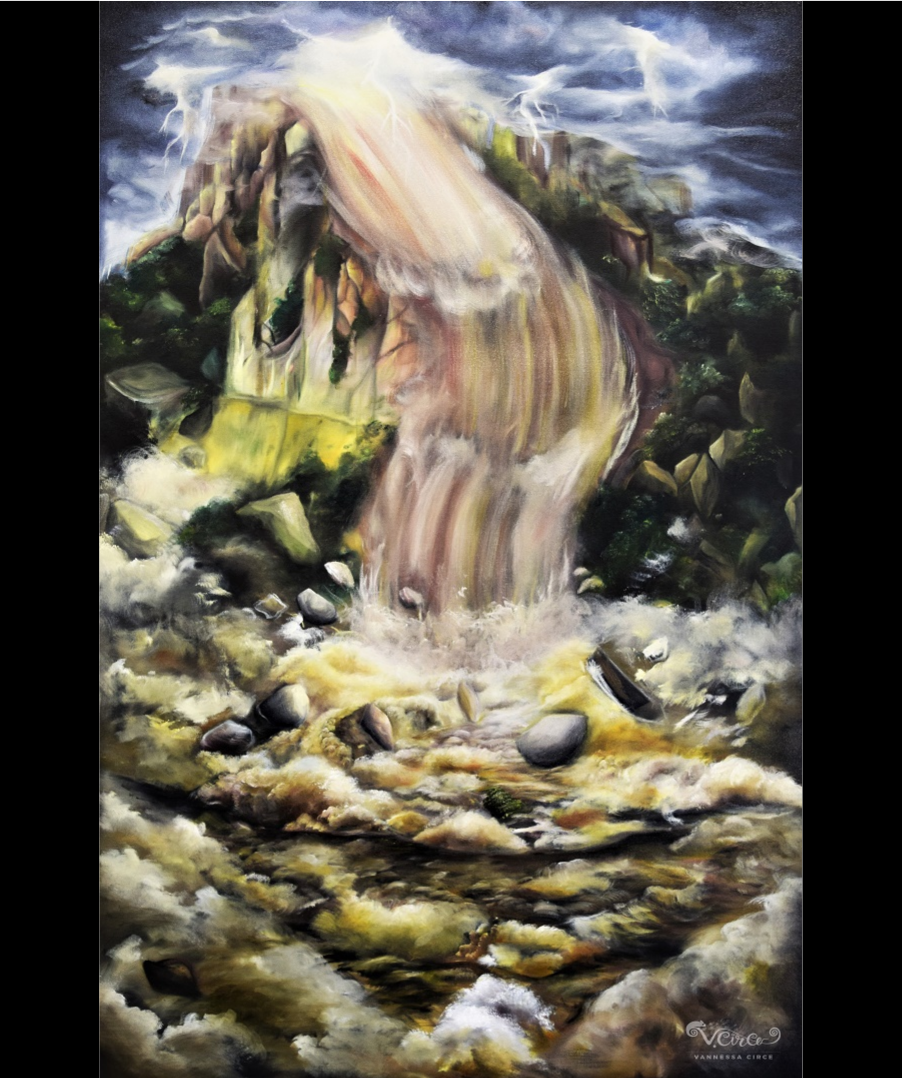

Oil on Canvas – 32” x 48”

April 2018

This painting was inspired by the events that transpired in Mocoa, Putumayo in March 2017, where more than 300 people, many indigenous, died in a flash flood and landslide after an uncharacteristically intense downpour. Over the past decade, the region around Mocoa, which is within the Colombian Amazon rainforest, has been heavily deforested for cow pasture and unsustainable agriculture. The weak and degraded soil was quickly washed into the rising river during the storm, taking trees, rocks and many other objects along with it. The water came rushing through the valley and destroyed hundreds of homes and lives. These dangerous floods and landslides are a consequence of climate change, deforestation and degradation and other unsustainable land use practices, and are becoming more common both in Colombia and around the world.

Oil on Canvas

30” x 40” – February 2018

Historically there were predictable periods of rain and dryness in La Guajira that followed equatorial weather patterns: there was the first dry season between December and April, followed by a short wet season from April to May, then an extended dry season from May to September and a final wet season from September to December. The Wayuu had local names for each of these seasons, with the main rainy season from September-December called “Juyapu.” Now these seasons are highly unpredictable, or do not exist at all. From 2012 to 2015, there was essentially no rain.

This kind of severe multi-year drought has predictable negative impacts on water availability and the well-being of wildlife, livestock, agriculture and the local populace. In La Guajira specifically, without rain, the jagueyes dry out, crops, cattle and natural flora and fauna die, and the Wayuu suffer. The cultural impacts on the Wayuu, who live by the rain and incorporate its presence into their beliefs and traditional practices, is less quantifiable, but also profound.

Desertification occurs on extremely degraded land, especially in drylands in semi-arid zones. Desertification is strongly connected to the extended droughts described above, and to unsustainable land use.

La Guajira is Colombia’s most rapidly desertifying region, for both of these reasons. The extended droughts and rising temperatures, the heavy use of the land for extractive industries, namely coal, and the damming of the principle waterways, makes “productive” use of the land all-but impossible.

In this painting, the scorched territory of the Wayuu in La Guajira is depicted, with a desperate attempt by young Wayuu children to sustain themselves and their culture through blocking a road with an extended handmade “chinchorro.”

Oil on Canvas

24” x 36” – January 2018

The term “Tropical Glacier” may seem somewhat counter-intuitive to those unfamiliar with their presence, but they exist because temperature decreases substantially with altitude, allowing precipitation to fall as snow, which accumulates and pressurizes over time as ice. However, as temperatures continue to rise due to climate change, the melting of Tropical Glaciers is due to worsen over the coming decades. This reality threatens aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems as well as the food and water security for tens to hundreds of millions of people.

Colombia has six remaining designated glaciers, in four distinct glacierized areas. The four areas are the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, the Sierra Nevada de El Cocuy, Nevado del Huila volcano and three glaciated volcanoes within Los Nevados National Park (Nevado del Santa Isabel, Nevado del Tolima and Nevada del Ruiz). The volcanoes of Los Nevados National park and Nevado del Huila are part of the Cordillera Central of the Andes, Sierra Nevada de El Cocuy is part of the Cordillera Oriental of the Andes and the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta is a coastal mountain range independent from the Andes. These glaciers have been losing ice mass for more than 150 years, since the “Little Ice Age”(LIA), but the scale and speed of this glacial melt has grown exponentially over the past 20-50 years.

Tropical mountain glaciers are rapidly melting around the world (up to 99% are in South America), but those that remain in Colombia could be entirely gone before 2050.

Oil on Canvas – 30” x 40”

November 2017

In this painting I show a tiny mollusk called a Pteropod, also known as a sea snail or sea butterfly, in the process of dissolving due to Ocean Acidification. The Pteropod forms the base of many marine food webs, so the consequences of its disappearance will reverberate up the food chain and affect many animals that depend on it for food, including the critically endangered North Atlantic Right Whale, which is displayed here in the distance through the dissolving Pteropod shell.

As part of the dissolution and death of the Pteropod, I also display bleached and dying Coral, another essential marine species that suffers greatly due to both rising Ocean temperatures and Ocean Acidification

Oil on Canvas – 36” x 48”

October 2017

A painting inspired by the circumstances of many displaced people and wild animals around the world, who must abandon their homes, territories, families and cultures as a consequence of violence, economic and natural exploitation and climate change.

In order to depict this global issue, I have three human models of refugees. There is a Sudanese woman and Syrian little boy, both victims of internal violence and conflict within their respective countries, and a Wayuu Indigenous Colombian girl. There are tens of thousands of Wayuu that have been forced from their land due to drought brought on by Climate Change and exploitation of natural resources and the damming of their principal waterway, the Rancheria river.

This painting was completed during my residency in Portugal from September – October 2017.

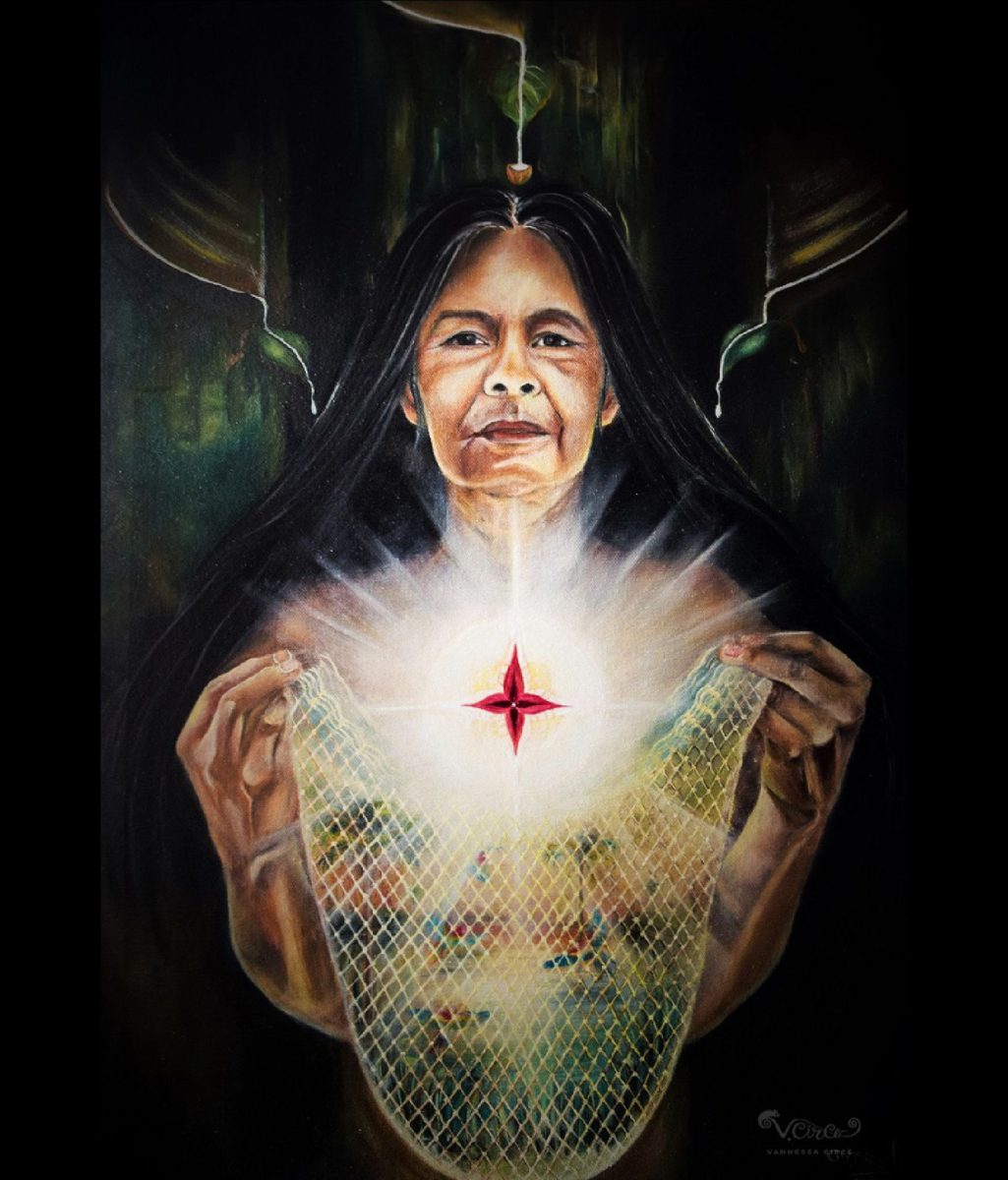

Oil on Canvas – 20” x 28”

May 2017

The model for this painting, Marina, is a Koreguaje woman who has been displaced multiple times from her territory in the Amazon in Caqueta, Colombia. The Koreguaje are a culture based on medicinal plants and agriculture, but have suffered from terrible exploitation of their lands for almost 200 years, starting with Quinine for malaria treatments, followed by Rubber, and more currently for the illegal drug trade and mining. In this painting Marina is seen with the flower of the Quinine tree, with the latex from the rubber trees behind her creating her torment. She is holding a handmade palm bag that inside shows the landscape from her beautiful home territory.

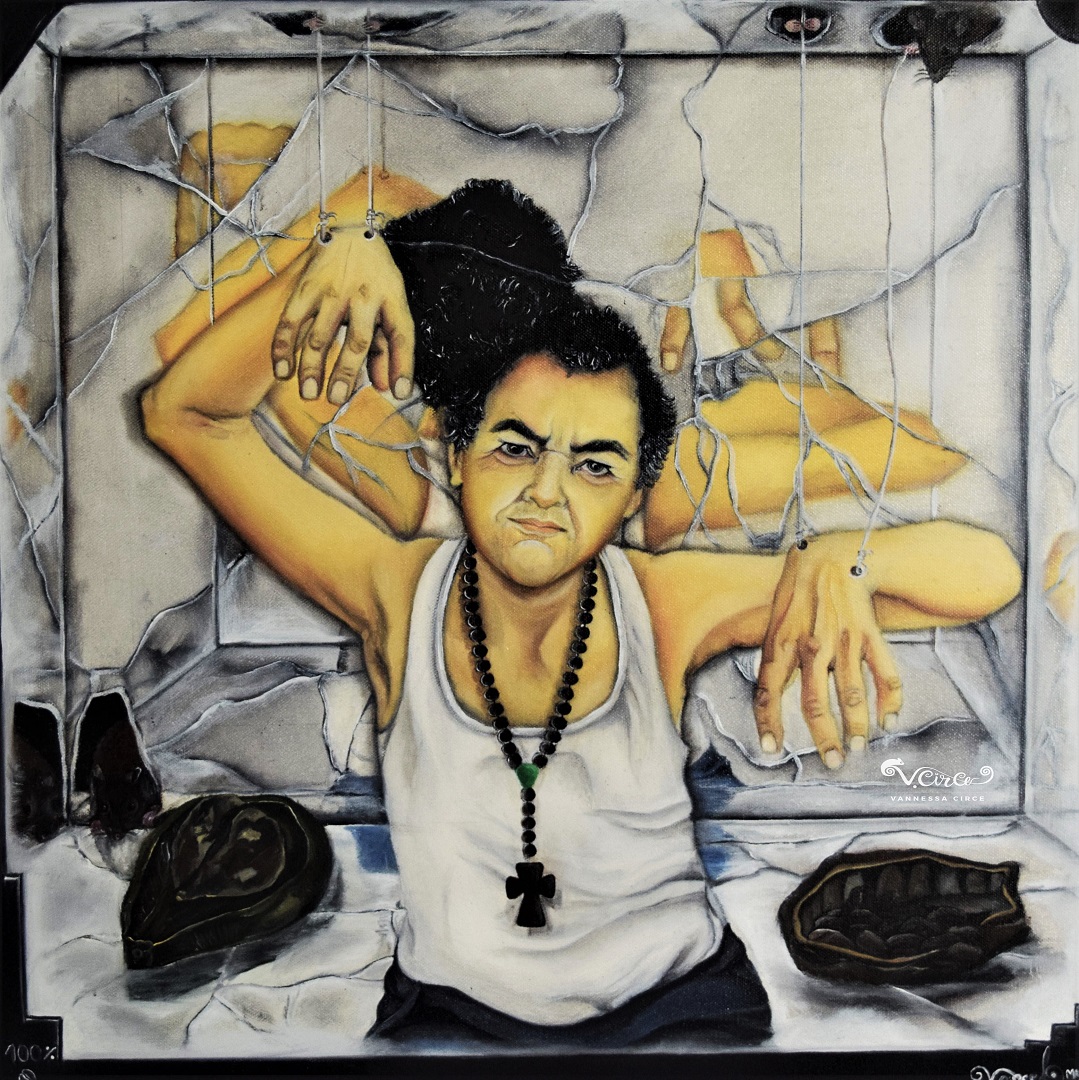

Oil on Canvas – 12” x 48”

March 2017

This is a conceptual symbolic painting meant to portray various degrees of insecurity, and uncertainty, that are taking place with our planet and with many cultures. In Colombia, specifically, a recent Internationally acclaimed peace deal signed in November 2016 between the Colombian Government and the Marxist FARC guerillas, is viewed in the eyes of many indigenous communities in Colombia with great uncertainty.

Power vacuums have resulted in areas where the FARC are disarming, and illegal bands and government sponsored paramilitaries that represent multinational interests, are already moving in to fill those vacuums, and violently silencing anyone who speaks up against them. Expansion of Oil Palm monocultures, which destroy forests and biodiversity, is a prime example of a recent trend. Colombia, with the “peace” has plans to vastly expand their Oil Palm industry, which is already the fourth biggest producer in the world and largest in the Americas.

Oil on Canvas – 24” x 28”

August 2016

For the Wayuu tribe of the vast desert region of La Guajira in Northeast Colombia, Pulowi is the female god of wind and destruction. The true destruction of the region, where thousands of Wayuu children die of malnutrition, is drought caused by global warming, and a massive coal mine called Cerrejon which has dammed the principal rivers of the region and caused horrible pollution to the remaining waters that do flow into the communities.

Oil on Canvas – 30” x 48”

April 2015

An exposition of the guerilla and paramilitary groups in Colombia, most notably the FARC, former AUC, and current “Bacrims,” and the fear and destruction that they force upon the very people they falsely claim to help; the poor and especially native people, groups of which more than six million are now displaced in Colombia. In this painting, we have Indigenous people from the Caldas region of Colombia, where the best coffee in Colombia comes from. They are being robbed, while in the background the extremely active Volcano, Nevado del Ruiz, is erupting. The indigenous child chooses to run towards the erupting volcano.

Oil on Canvas – 20″ x 20″

February, 2015

A painting representing disenfranchised native Colombian people.

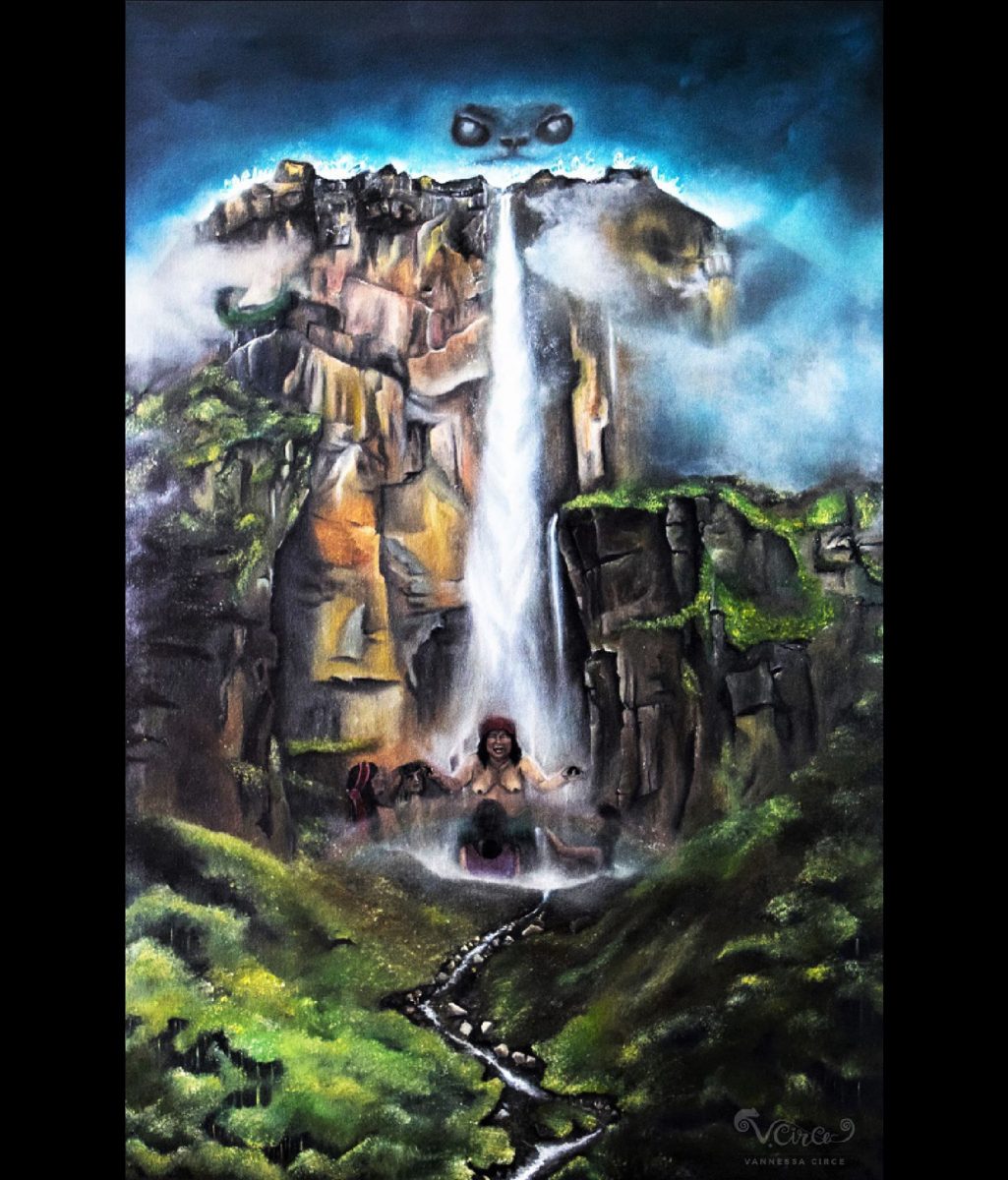

Oil on Canvas – 37″ x 25

January, 2015

The Yanomami people live in the Tepuyes of Venezuela. The painting shows the vulnerability that many indigenous peoples of the world suffer.

Oil on Canvas – 20″ x 24″

September, 2014

Atrocities of war can occur in and by any culture, at any time, in any place, given proper indoctrination, and those horrors can live on through generations. The My Lai massacre, in which United States “soldiers” slaughtered upwards of 504 defenseless woman and children on March 16th, 1968, is a perfect case in point, and the inspiration for this painting. These US soldiers had been convinced that even the babies were booby-trapped with grenades, and carried out their orders in such barbaric fashion that the wounds of those in Vietnam today with any ancestral connection to this tragic event, still feel fresh.